I had the good fortune to attend a recent performance of The Spirit Horse Returns, an engaging and educational production by Jodi Contin, Rhonda Snow, Ken MacDonald, the NAC Orchestra and NAC Indigenous Theatre. Event-goers young and old alike learned about the endangered Spirit Horse (also known as the Ojibwe pony and the native pony), who has accompanied Indigenous people since time immemorial on Turtle Island.

The masterful storytelling of Indigenous knowledge-keeper Jodi Contin, visual cues on a projector screen, colourful artwork by Rhonda Snow, and a tuneful orchestral score conducted by Naomi Woo kept the attention of many families in attendance for 75 minutes.

Before the event, Snow organized multiple tables of activities in the main lobby of the NAC, including free pendant-making, collaging, and colouring her works of the Spirit horses.

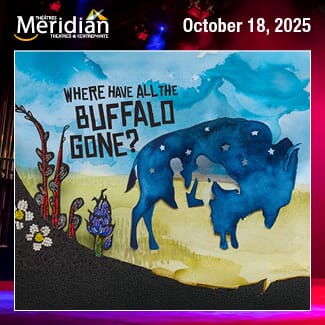

Artwork by Rhonda Snow. Photo: Sonya Gankina.

Jodi Contin is a hand drum maker of 20 years. Ken MacDonald plays the French horn professionally and runs his family’s 13th-generation farm, where he now has multiple Ojibwe ponies. Together, they created The Spirit Horse Returns back in 2017. It’s rare to pair the Indigenous hand drum with the orchestral French horn—yet the pair found harmony and performed together during the Parry Sound Festival. During that time, Ken introduced Jodi to his Spirit ponies for the first time. Before that, Jodi had never seen them before.

Inspired by the connection she felt with the ancient breed, she created a song and sang it for Ken. The storytelling festival included the song and the real horses in its programming, and the kids loved it. Jodi and Ken have been performing together since then. “The show is modular, people come in and out and we welcome them,” adds Jodi, “It’s a unique aspect of the production.”

Jodi Contin and Ken MacDonald. Photo: Curtis Perry.

The production tells the tragic story of the Spirit Pony. Since the beginning of time, the ponies, which are smaller and shorter in stature compared to the European draft horse, accompanied the Indigenous people on the land. Also known as the “Lac La Croix Indian Pony,” this breed is considered semi-feral because the first people never tied them up and the ponies grazed across the land freely, willingly interacting with people of their own accord. The pony takes its name from the Lac La Croix First Nation in Ontario, where it was last found in the wild.

When the settlers came and brought large farm horses with them, they saw no need for the Ojibwe ponies and considered them useless for tough farm work. Yet, during the gold rush of the late 1800s, the big draft horse proved impractical to take into the mountains and forests to hunt for gold. The settlers took the Indigenous peoples’ ponies by the thousands into perilous conditions and many died.

Their plight didn’t end there. When the free horses were grazing farmers’ fields, many were shot. By 1977, only four mares remained. When Canadian health officials deemed the horses a health risk and planned to destroy them, five men rescued the mares and drove them across a frozen lake to a reserve in Minnesota. Since then, the mares have been bred with Spanish mustangs to preserve the breed, and today about 150 horses live in sanctuaries in Canada and the United States.

The Spirit Horse Returns. Photo: Curtis Perry.

The horses are significant spiritual symbols to Indigenous peoples and their extinction would have been horrific. The spiritual connection is palpable to this day: one time, Jodi says she went to Ken’s farm and met a Spirit Pony called Asemaa’ikwe (tobacco woman in Ojibwe). She began hand-drumming and singing and the Spirit horses came running at her at full speed. When she stopped singing, they stopped in their tracks. We saw the exact video of this experience during the performance—it was breathtaking.

“I felt a special connection in that moment,” shares Jodi. “It’s a healing song and in the song it talks about the beautiful spirit that resides in the horse as a healer to all people. When you touch its forehead, you’re connecting with it. It will give you what you need and take away what you don’t need. They come to you when you sing to them—they feel us, our energy, when we talk to them in Ojibwe. When I spend time with them, it reminds me of the work we are supposed to be doing for the Anishinaabe.”

NAC Southam Hall. Photo: Sonya Gankina.

“I want people to have an open mind and an open heart to this way of life,” says Jodi of her intentions for the production. “Be kind to each other and follow the seven grandfathers as we walk the Turtle Island together through this time where we’ve never been before. I’m grateful for this opportunity—this is huge for our people and our horses. This is history being made.”

You can meet nine Spirit Ponies at Ottawa’s very own Mādahòkì Farm. Every person, Indigenous or not, can support the conservation efforts of this special Canadian breed.