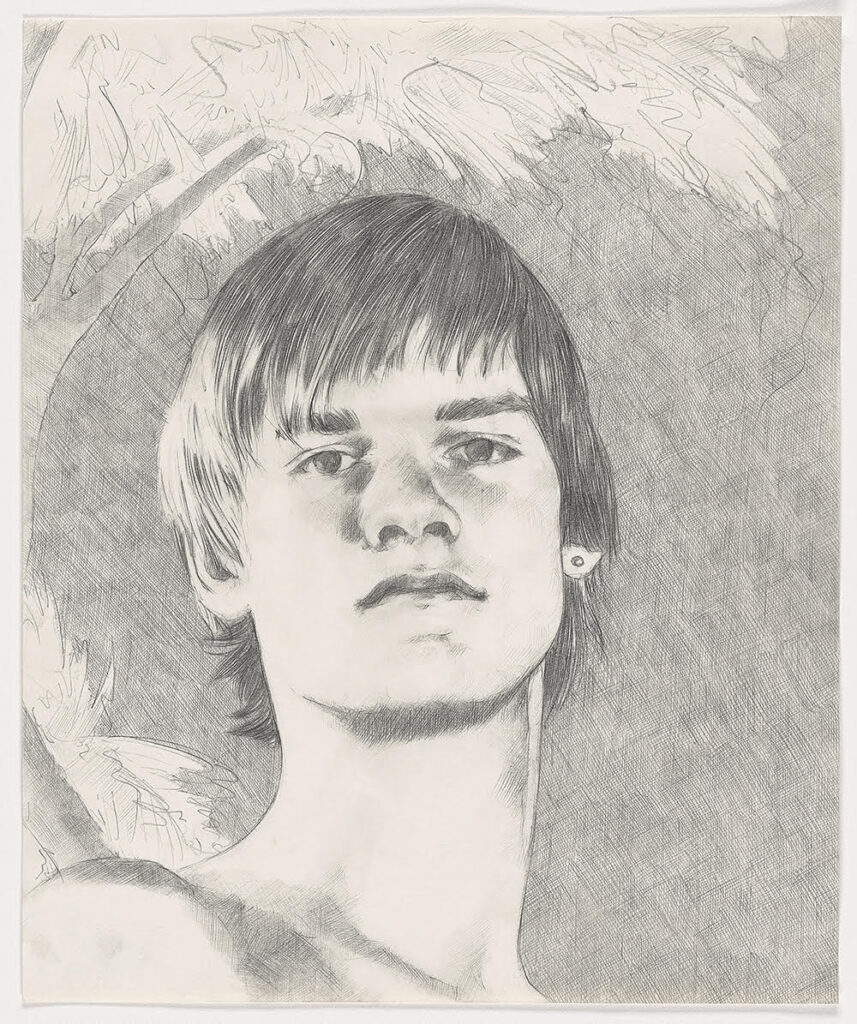

The detailed crosshatching on the 2003 “Untitled” portrait by Toronto artist Paul P. represents a dedication of “deep care” evidenced in delicate graphite strokes. Drawing this way provided new means of looking, a way he could see and understand more. Within the pages of gay erotic magazines, he says he saw heroes similar to himself and queer men he knew; many were depicted before the AIDS crisis of the 1980s.

Paul P. Untitled, 2003. Graphite on wove paper, 33.5 × 27.8 cm. National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa. Purchased 2020 with the generous support of Diana Billes, Toronto. (49026) © Paul P. Photo: NGC

The environment P. worked in has always been one of openness. It wasn’t always the same for the artists displayed next to 30 of his works in the National Gallery of Canada (NGC)’s latest Paul P. exhibition. Those creative minds, dating back to the 16th century, faced repercussions if their depictions of homosexuality became known—from social ostracization to imprisonment. Still, they defied “the prevailing morality of their time and furthered a secret language of coded homosexuality,” according to NGC staff.

Amor et Mors, the exhibition’s title, translates to “Love and Death” in Latin—an inversion of the title “Mors et Amor” (“Death and Love”) by symbolist painter Simeon Solomon from 1865. Solomon’s ink drawing is included in the exhibition and depicts two figures embracing one another; the first is next to a hooded figure by the word “death” and the other beside a winged figure beside the word “love.” Artists like Solomon, who was later arrested for homosexual acts, could share expressions of homosexuality in such veiled ways.

Simeon Solomon. Mors et Amor (“Death and Love”), 1865 pen and black ink and red chalk over graphite on wove paper, 25.3 × 36.4 cm. National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa. Gift of the Dennis T. Lanigan Collection, 2017 (48437) Photo: NGC

Some of the queer themes artists explored used both implicit and explicit language. P. says the precise codes of these artists were difficult to pin down, “but they are those things that allowed the work to be accepted and not destroyed, given safe passage.” These artists would pull on threads from well-respected ancient Greece and mythology. Solomon’s work, for example, embodies these covert techniques.

P. says: “He was extremely adept at using not only classical, but Jewish and Christian mythology and just skewing it slightly and making it therefore legible to the people that he was speaking to— other homosexuals and artists and people in his group who might be sensitive, but also, at the same time, keeping it inscrutable to the censors—the people who might wish him harm.”

P. created several of his own ink drawings within galleries where he was inspired by neoclassical sculpture, which used various hidden codes. Eventually, queer artworks moved to more explicit forms of depiction, says P: “The quality of fleetingness inherent to life lived under the threat of punishment has led me to appreciate the temporal and other forms, from sunsets to the precarious psychological and physical attitudes of neoclassical sculpture to the play of light and cast,” he adds. However, his own work is varied. P. expanded to portray abstract and mysterious landscapes, plus furniture sculptures throughout his career.

Paul P. Untitled, 2011 watercolour on wove paper, 28.9 × 16.6 cm. National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa. Purchased 2020 with the generous support of Diana Billes, Toronto. (49032) © Paul P. Photo: NGC

“Paul is, to my mind, an artist-cum-art historian, which is perhaps why we took so much pleasure in working together,” said Sonia Del Re, NGC senior curator of prints and drawings.”His practice mines the past in search of queer aesthetics, narratives, and visual strategies.” It’s the first time she’s curated a living artist in almost 20 years. Amor et Mors also includes works from James Abbott McNeill Whistler and lovers Charles Ricketts and Charles Shannon.

P. says that the stories from these artists “are not old or new.” He explained to Apt613 that he “felt compelled to look at queer history more broadly—in particular, those periods that were not so permissive, and by calling attention to those eras of criminalization and censorship, perhaps allows artists and viewers today to understand that the implicit representation of queer desire was a strategy of resistance that remains useful for us to study.”

Amor et Mors is on display at the National Gallery of Canada until June 11, 2023.