Barber Street, Lowertown, Ottawa. Photo by Ashley Newall.

Paul J. Barber (1893–1958) was everybody’s favourite kind of person—a character. Funnily enough, he lived in my own Lowertown neighbourhood, a mere block from my current abode, on a former section of Clarence Street now named for his father, another Paul Barber (1848–1929), who was born into slavery in Kentucky.

Paul Sr. first appears in Ottawa’s city directory in 1887 and was a highly regarded horse trainer (a skill he learned in Kentucky). His 1892 marriage to Elizabeth Brown, who was white, was the first known interracial marriage in Ottawa. Consequently, Paul Jr. was mixed-race.

Horse race on the Ottawa River, 1902. Paul Barber Sr. trained horses for these popular races.

Paul Jr. was a long-time “newsie” on the northwest corner of Bank and Sparks Streets. Among his regular customers were prime ministers R.B. Bennett and William Lyon Mackenzie King. Due to Paul’s proximity to the press—as well as his various exploits in general—he appeared in newspapers far more often than your average Joe, making my job here that much easier.

“In soft cloth cap, on or off his motorcycle, which was his favourite mode of travel, Mr. Barber was an integral part of the downtown Ottawa scene …. He was 12 when he “opened for business” in 1905 at the corner of Bank and Sparks Street, under the friendly protection of Harry G. Ketchum, who owned a sporting goods store [Ketchum & Co.] where the Regent Theatre now stands.” (Ottawa Citizen, May 22, 1958)

Ketchum & Co. Sporting Goods, northwest corner of Bank and Sparks Streets, Ottawa, 1905. (Present-day site of the Bank of Canada Museum.) What is believed to be Paul J. Barber’s newsstand is circled. Original photo via Library & Archives Canada; colourized by Ashley Newall.

“Known familiarly as ‘The Voice’ because of the way he called out the headlines, Mr. Barber was always a great champion of newsboys. His seven sons were among the hundreds of boys who worked for him over the years. He always split 50-50 with his boys and was often seen when the day’s work was done going home with six or seven youngsters draped over his motorcycle and sidecar.” (Ottawa Citizen, May 22, 1958)

A founding member of Ottawa’s Motorcycle Club in 1917 (and serving on its executive committee), Paul reportedly owned the first motorcycle in the city. Two months after the club was founded, he enlisted in the First World War.

Private C. M. Johnston, C.A.S.C., 1917. Photographer unknown.

This story was initially intended to be about the segregated No. 2 Construction Battalion. While many Ottawans served in the No. 2, they were all white officers—I couldn’t find a single Black recruit from Ottawa in the entire battalion. Roughly half of the Canadian Black men who served in WWI did so in the No. 2 Battalion, about which much has been written in recent years, and for which the federal government recently issued a formal apology. (The unit is said to have numbered 780, although it’s unclear whether that number includes the white officers.)

Black soldiers loading Canadian Corps Tramways with ammunition, 1918. Original photo from Library & Archives Canada; colourized by Ashley Newall.

While the conflict was trumpeted as a “white man’s war” at the time, a reported 700 Canadian Black men did serve in non-segregated units (including in combat roles, in an unknown or unclear number of cases), including the four Post brothers from Ottawa.

“James Post enlisted on 25 July 1915 and served with the 4th Battalion, Canadian Mounted Rifles. He was still underage when he was awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal (for ‘conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty’ at Passchendaele). His brother Joseph was also underage when he enlisted in Valcartier on 22 September 1914. He was later awarded a Military Medal.” (“Black Volunteers in the Canadian Expeditionary Force,” The Canadian Encyclopedia)

Paul Jr. signed up in the immediate wake of the very contentious Military Service Act (i.e. conscription) coming into effect, reportedly ignoring his doctor’s orders against enlisting. He’d tried to sign up for the 80th Battalion previously, but was rejected for reasons that were “unknown” to him, as per his Sept. 20, 1917 attestation. He listed his trade at the time as chauffeur (driving newsboys by motorcycle to and from the news stand, perhaps?), and his attestation is stamped “C.A.S.C. (Canadian Army Service Corps) Mechanical Transport.” His complexion is listed as “Dark”, and there’s a footnote: “(Negro).”

Canadian Army Service Corps recruitment poster. Library & Archives Canada.

Regarding Black Canadian enlistment in the First World War, Kevin McGaw of the Vimy Foundation explains: “The Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF) did not have a distinct segregation policy like the American Army at the time” but “left it at the discretion of the recruiting officer to accept recruits of different races or not.”

This led to Black Canadians often being declined for combat units, but many were subsequently enlisted in the various service corps (a.k.a. “labour units”), such as the Forestry Corps. Similarly, some were also reportedly (and evidently) enlisted in the C.A.S.C.

Recruitment ad for the Forestry Battalion, 1916. Library and Archives Canada.

Paul Jr. arrived in England in March 1918, and landed in France that July. He served out the war, which concluded in Mons, Belgium, for the Canadian Army.

Back in Ottawa, in 1926, he participated in an Ottawa Journal company hockey game at Dey’s Arena that pitted the staff bachelors against the married men. (Paul landed in the latter category.) It was noted that “Paul Barber was a stonewall on the defense and had little trouble stopping all the opposing forwards … The game was cleanly played, only four penalties being handed out, Paul Barber receiving all of them.” (Ottawa Journal, Jan. 14, 1926)

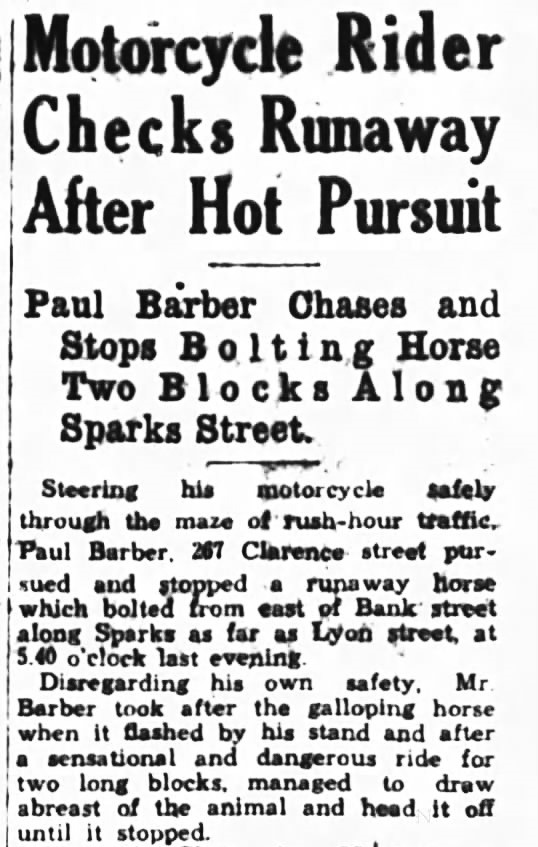

In 1930, Paul Jr. was involved in an interesting high-speed chase—he was on a motorcycle chasing a horse.

Ottawa Journal, Oct. 18 1930.

Also in 1930, Paul Jr. took part in a “fancy dress” skating carnival competition at Cartier Square, with Governor-General Lord Willingdon and Lady Willingdon in attendance, ultimately placing second in the “complimentary class” (the exact meaning of which is unclear, but the first-place winner in the category also won the grand prize for best costume). The competition had a decidedly racial edge, and yet was also evidently inclusive. The men’s division winner was noted to be wearing “a liberal quantity of stove black on his face,” while a presumably Indigenous participant who hailed from the Golden Lake Indian reserve wore “full tribal costume.” Finally, and interestingly, the men’s comic class winner had his face “heavily rouged to imitate the sunburn of a yokel.” (Ottawa Journal, Feb. 5, 1930) Suffice it to say, there were few stones left unturned.

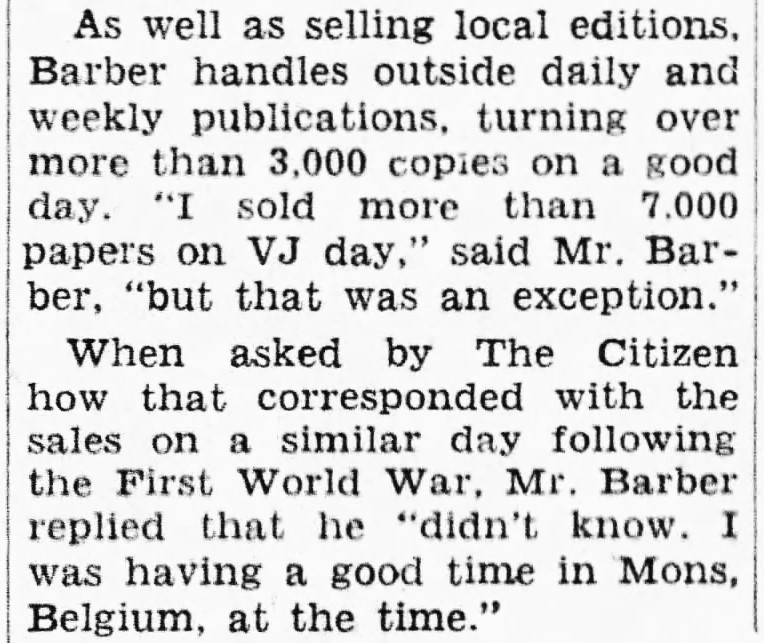

In 1948, in celebration of his 40th year as a newsie (factoring in the time he spent in the C.A.S.C.), Paul Jr. was featured in the Ottawa Citizen:

Ottawa Citizen, Aug. 10, 1948

He didn’t quite make it to his 50th anniversary as a newsie, passing just a few months shy. “The Busy Corner” of Bank and Sparks would never be quite the same again.

Sparks St looking west from Bank, showing Regent Theatre (ca. 1938). Original photo from Library & Archives; colourized by Ashley Newall.

You can follow Ashley Newall’s Capital History Ottawa on Instagram, Threads, and X/Twitter.